of the Australian troops |

|

Japanese reconnaissance aircraft |

The USS Lexington at the Battle of the Coral Sea |

The "Golden Stairs" climbing to Imita Ridge were cut into the Track after the 39th Battalion first crossed the mountains |

The 39th Battalion at Menari, 1942 |

The track near Oivi, between Kokoda and Wairopi |

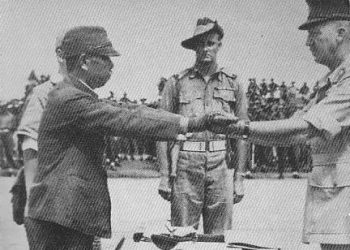

Lieutenant-General Adachi, commander of the Japanese 18th Army in New Guinea, hands his sword to Major-General H.C.H. Robertson of the 6th Division after signing the surrender documents at the Cape Wom airstrip |